In the last few years, the world has begun a more definitive transition from the place of cynicism and misunderstanding about the issue of Climate Change to that of warmer realisation, if not wholesome acceptance, of the reality of the phenomenon as a significant threat. But then, even in the face of a whittling down of opposition against the science of climate change, with the pushback against efforts to mitigate it not as fierce as it once was, agreeing on a framework with universal acceptance, embedded with individual contours, has been rather difficult. That is not a surprise given the different, and often, competing realities among countries.

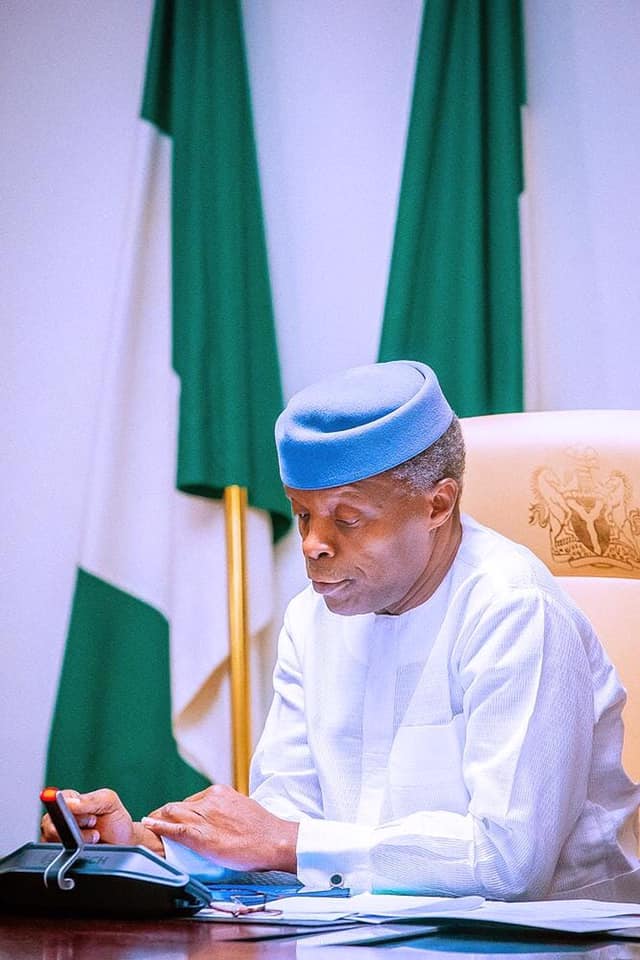

Indeed, there is no way the issue of climate change can be addressed on a sustainable basis without putting into the mix the conjoined issues of energy inequity, energy poverty, and energy access. “For Africa, the problem of energy poverty is as important as our climate ambitions. Energy use is crucial for almost every conceivable aspect of development. Wealth, health, nutrition, water, infrastructure, education, and life expectancy are significantly related to the consumption of energy per capita,” Prof Yemi Osinbajo, Nigeria’s Vice President argues.

In August this year, the Nigerian government launched the Energy Transition Plan to address the issues of climate change and energy poverty. Having accepted that climate change is a reality and threat to crop productivity, with the potential of further worsening unemployment, the government commits itself to an urgent plan of action, which requires putting an end to energy poverty by 2030 and achieving net-zero by 2060. In fact, President Buhari had committed to this in a statement at COP-26 in Glasgow.

However, on the back of that commitment is the realisation that “the average $3 billion per year investments in renewable energy recorded for the whole of Africa between 2000 and 2020 will certainly not suffice,” as this is a plan that requires huge resources and funding that cannot come through the regular window. The energy transition plan will require an estimated $1.9 trillion in finance, which includes $410 billion above business-as-usual spending, to the tune of $10 billion annually till 2060.

According to the African Development Bank (AfDB), Africa is not only losing 5-15% capital economic growth, but also facing a shortfall in climate finance, as Africa benefits less than 5.5% of global climate finance. Between 2016 and 2019, African nations only received around $18.3 billion in climate finance. While the industrialised world had promised in 2009 to deliver $100 billion in climate financing to the developing world, that pledge has only been redeemed in part. Yet, another gap of about $1.3 trillion has been identified for 2020-2030.

It is against the backdrop of the challenges posed by climate change and the obvious finance gap that confronts Africa that makes the idea by Vice President Yemi Osinbajo for Debt-for-Climate Swap a compelling proposition for consideration. In a lecture on a just and equitable energy transition for Africa he delivered at the ‘Center for Global Development in Washington D.C, USA,’ he made the argument that the issue was not only one of just transition but of two existential crises – “climate crisis and extreme poverty.” For that reason, whatever plans and commitments made towards carbon neutrality “must include clear plans on energy access,” he argues. Further to that, in order to confront poverty, there must be “access to energy for consumptive and productive use,” he says.

Osinbajo spoke to the disparity of energy access between the developed and developing world in graphic terms. Africa with about 17% of the world’s population only generates 4% of the world’s electricity. Whereas the one billion people in Sub-Saharan Africa, excluding South Africa, are serviced by an installed capacity of 81 gigawatts, “the United States has an installed capacity of 1,200 gigawatts to power a population of 331 million people, while the United Kingdom has 76 gigawatts of installed capacity for its 67 million people. The per capita energy capacity in the United Kingdom is almost fifteen times that in Sub-Saharan Africa.”

While developing countries are faced with the constraint of energy poverty, striving to increase capacity and improve on energy access to drive industrialization and development, they are compelled to take into consideration the demands or expectations that come with mitigating climate change. As Osinbajo notes, “…in the wider responses to the Climate crisis, we are not seeing careful consideration and acknowledgement of Africa’s aspirations. For instance, despite Africa’s tremendous energy gap, global policies are increasingly constraining Africa’s energy technology choices.”

In fact, there has been advocacy or implementation of “policies on limiting public funding for fossil fuel projects in developing countries, making no distinction between upstream oil and coal exploration; and gas power plants for grid balancing.” Yet, in the face of global energy crisis, some of the countries in Europe have made a move to “increase or extend their use of coal-fired power generation through 2023, and potentially beyond,” in disregard or violation of their climate commitments, which analysts suggest “will raise power sector emissions of the EU by 4%, a significant amount, given the high base denominator of EU emissions.”

While there is no doubt that every country, by virtue of policies and activities, has its impact on cumulative global carbon footprints, the level of impact is remarkably different from one country to the other. It is estimated that about 80% of all emissions in the world come from only 20 countries, with Africa contributing only 2–3 per cent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions from energy and industrial sources.

Despite the disproportionate nature of carbonization with only minimal carbon footprints generated by less-industrialised countries like Nigeria, the government has launched an ambitious energy transition plan that commits her to the decarbonization of Nigeria’s energy sources and future, with objectives that include “lifting 100 million people out of poverty in a decade, driving economic growth, bringing modern energy services to the full population and managing the expected long-term job loss in the oil sector due to global decarbonization.”

Whereas there is greater interest on the part of the developing world to contributing their quota in the drive for a carbon-free globe, there is also the desire to be more involved in the formulation of strategies and transition pathways in line with the objectives of the countries themselves and Sustainable Development Goal 7, which pushes for universal access to clean and affordable energy.

Targets set out in Nigeria’s Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) include: 20% conditional and 45% unconditional emissions reductions; establishment of 13 GW of off-grid solar PV; an increase in energy efficiency by 30% by 2030; and an end to gas flaring by 2030. There are also measures and strategies to promote reforestation, Climate Smart Agriculture, to make agriculture a more sustainable and productive venture; and the sustainable use of resources through programmes that promote alternative means of livelihood. The project also has incorporated within climate adaptation policies and biodiversity conservation.

However, beyond the intentions and commitment on the part of developing countries, noble as they might be, the question of financing energy transition away from carbon is a sticky one, especially within the larger context of the economic condition of the countries, made worse by the overwhelming realities of Covid-19. As Singh and Widge note, since “a greater proportion of these governments (now reduced) revenues are now dedicated to servicing debt, spending towards reviving growth or achieving climate goals will likely take a backseat.” They propose fiscal headroom for countries caught in such a situation through the mechanism of either “debt suspension, debt forgiveness or reorientation of debt so that service payments are utilized for a green recovery.”

Debt for Climate (DFC) swaps, which began to gain currency in the last two years, “are a type of debt swap in which the debtor nation, instead of continuing to make external debt payments in a foreign currency, makes payments in local currency to finance climate projects domestically on agreed upon terms. DFC swaps can reduce the level of indebtedness as well as free up fiscal resources to be spent on green investments…Alternatively, new debt can be issued by a debtor nation to replace existing debt with a commitment to use proceeds to address climate change through mutually agreed performance-linked incentives such as lower interest rates, grants, carbon offsets to service interest, etc.”

The essence of the debt for climate swap is to engender an “increase the fiscal space for climate-related investments and reduce the debt burden for participating developing countries.” Indeed, the idea of Debt as a Climate Change-related financing instrument is not new but the argument as presented by Vice President Osinbajo has enlivened and elevated it. His presentation at CGD and subsequent engagement with Vice President Kamala Harris of the United States of America, as well as other government officials have pushed up and energised the conversation. He has succeeded in placing side by side the twin issues of energy poverty and climate change, arguing not only for them to be considered together, but for African nations to be more critically engaged in conversations on the global climate future and take ownership of their transition pathways.

Osinbajo specifically argues for Africa to fully participate in the global carbon finance market, in addition to conventional capital flows both from public and private sources. “Currently, direct carbon pricing systems through carbon taxes have largely been concentrated in high and middle-income countries. However, carbon markets can play a significant role in catalyzing sustainable energy deployment by directing private capital into climate action, and improve global energy security, provide diversified incentive structures, especially in developing countries, and provide an impetus for clean energy markets when the price economics looks less compelling – as is the case today. So, supporting Africa to develop into a global supplier of carbon credits, ranging from biodiversity to energy-based credits, would be a leap forward in aligning carbon pricing and related policy around achieving a “just transition.”

There is no doubt about the increasing coincidence of realization on the part of both the developed and developing world that climate change is indeed an existential challenge. Also, there is no doubt about the urgency of the situation and the necessary actions that need to be taken. All African countries have signed onto the Paris Agreement, with Nigeria and a few other countries in Africa having also announced a net-zero target, in firm commitment to a decarbonized energy future. The challenge is with financing climate and clean energy plans for developing countries like Nigeria in the face of a climate finance shortfall and the problem of energy poverty. That is what makes the Osinbajo argument of swapping debt for climate financing a compelling proposition, if every country is to be carried along in putting the right foot forward on the decarbonization drive.

However, questions have been raised about the idea. Is the Debt for Climate Swap Deal really a good idea? What are the possible challenges? How can all concerned be brought together to be on the same page with intended outcomes? What about the question of size and structure? Which countries constitute the target? Who are the likely creditors? To Chamon et.al, “because some of the benefits of debt-climate swaps accrue to non-participating creditors, they are generally less efficient forms of support than conditional grants and/or broad debt restructuring (which could be linked to climate adaptation when the latter significantly reduces credit risk)”.

Vikram Widge believes that a debt swap for climate financing will be more meaningful where there is direct negotiation between borrower and lender. Taking into consideration that China is a major bilateral official creditor, there is not much that can be done with respect to swap arrangements without engaging with China and securing its support. To Widge, “…to be successful at scale and mobilize significant capital, debt-for-climate swaps should probably focus on countries that are able to service their debt, and who – in exchange for some reduction/forgiveness of the debt as an incentive – would be willing to redirect the debt service cash flows into mutually agreed use of proceeds from the swap. In this arrangement, target countries are likely to be the larger emerging market borrowers that are working toward ambitious climate action plans but need extra help here.”

Chamon et.al argue that “debt-climate swaps could be superior to conditional grants when they can be structured in a way that makes the climate commitment de facto senior to debt service; and they could be superior to comprehensive debt restructuring in narrow settings, when the latter is expected to produce large economic dislocations and the debt-climate swap is expected to materially reduce debt risks (and achieve debt sustainability). Furthermore, debt-climate swaps could be useful to expand fiscal space for climate investment when grants or more comprehensive debt relief are just not on the table.”

It is instructive that more voices are being heard in support of the debt-for- climate swaps. The U.N. Deputy Secretary-General, Amina Mohammed, ahead of the ongoing U.N. Climate Change Conference in Egypt made the point that “countries need options to refinance crippling existing debt, including debt for climate adaptation swaps, where vulnerable countries can reduce their debt stock and free up resources for adaptation.” The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA), one of five regional commissions under the jurisdiction of the United Nations Economic and Social Council, piloting with Jordan and other countries, has come up with an initiative tying Climate with SDGs and debt swap. The essence of the initiative is to “address the challenge of reducing debt burden, improving climate finance and accelerating Implementation of the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda.”

Also, there has emerged a group known as V20, made up of 58 countries (Nigeria excluded) deemed to be the most vulnerable to climate change, with only 5% share of global emissions, a population of 1.5 billion people and GDP valued at USD 2.4 Trillion. Ahead of Cop27, they were considering “a plan to stop payment on a combined $685 billion in debt until the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank address climate change the way their nations see fit.”

There is no doubt that the idea of a debt-for-climate swap is no longer one that can be easily waved away. Indeed, there is no denying the grave impact of climate change, which sees 15 million people dying annually on account of the poor quality of air from pollution and another 5 million dying as a result of extreme heat. There is the question of future demand for energy compounding the current energy poverty, which is a threat to the lives and livelihoods of millions of Africans. There is also the question of Nigeria’s methane pledge to end gas flaring and yearning to take more advantage of its gas reserves to meet domestic energy need, among other options. Yet, there is the commitment to decarbonization that she has made, even in the face of a yawning financing gap. The most feasible route to the resolution of these questions, some of them contending, is to design a template for climate financing via debt swap, which will be adopted and adapted to suit the different circumstances across bilateral and multilateral platforms. That will serve Nigeria and the world well.